Thomas Edison a.k.a. The Movie Mogul Who Started LOLcats

Lightbulbs are nice, but it was Edison’s kinetoscope 115 years ago today that brought us Hollywood and boxing cats

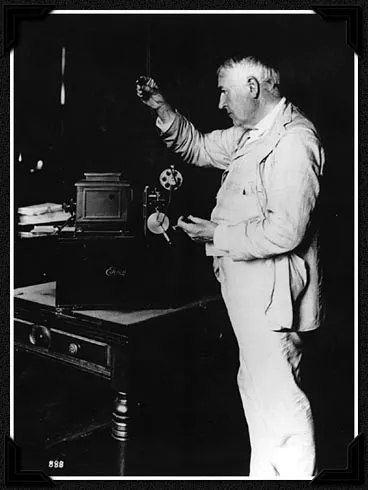

When inventor Thomas Edison first began toying with the idea of improving upon moving image technology, he filed a note with the patents office in 1888, expressing his intent. He wrote that he hoped to invent a device that would, “do for the eye what the phonograph did for the ear.” When he finally invented (with considerable help from his assistant, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson) and patented his single-camera device 115 years ago today, August 31, 1897, Edison was well on his way to launching the American film industry and even predicting America’s fascination with cats doing things on film.

Though Edison had received a visit from one of the early pioneers of moving pictures, Eadweard Muybridge, he turned down the opportunity to work with him, according to the Library of Congress and research from historians Charles Musser, David Robinson and Eileen Bowser. Sure, Muybridge had developed a way to use multiple cameras to capture a series of movements and then project is as a choppy but recognizable motion. But Edison didn’t think there was much potential in the multi-camera approach. Instead he labored (well, supervised others laboring) for three years to invent a single camera, the Kinetograph and single-user viewing device, the Kinetoscope, to record and view moving image in 1892.

Other than being a talented inventor, Edison also had the resources to attract other great talent, including Dickson, who moved his entire family from France to Edison’s research lab in Menlo Park, New Jersey. Smithsonian curator Ryan Lintelman explained in a 2010 podcast, “By the 1880s Edison became known as “the Wizard of Menlo Park” because these inventions that he was coming up with were so transformative that it was as if magic was involved.”

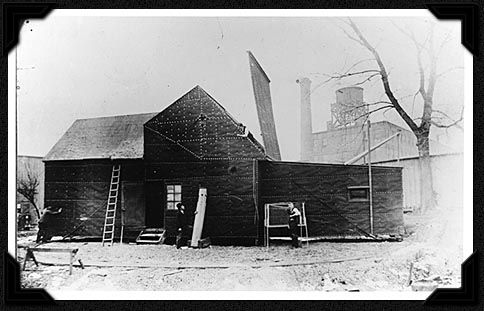

It wasn’t long after the kinetoscope’s invention that he began producing movies under his own studio, nicknamed the Black Maria because the structure that housed it resembled a police patrol car. Ever the businessman, Edison oversaw the production of star-studded shorts to help popularize his invention, including films with Annie Oakley, acts from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and Spanish dancer Carmencita. His subjects tended toward the sexy or the strong, proving the adage that sex sells. But one short titled The Boxing Cats (Professor Welton’s) also shows Edison’s ability to predict the insatiable market for watching cats do things, like fight each other in a tiny boxing ring.

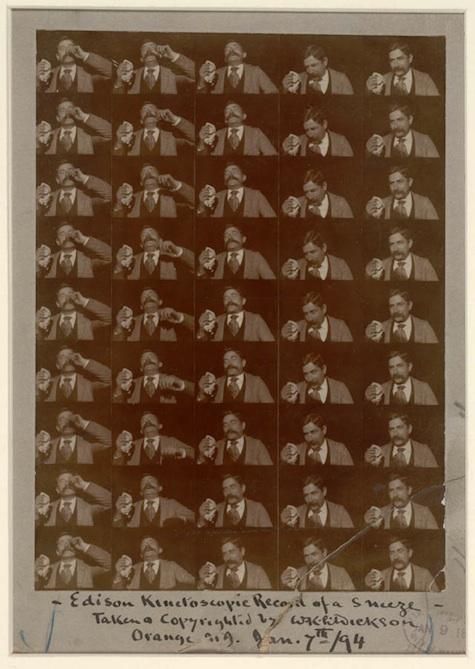

“These first films they made for audiences were just short, simple subjects like women dancing or body builders flexing or a man sneezing or a famous couple kissing, and these early films have been called “the cinema of attractions” because they were shown as sort of these amazing glimpses of new technology rather then narrative plays on film,” explained Lintelman.

Unfortunately, the earliest surviving film from his studio is a little less titillating than the late 19th century equivalent of Brangelina kissing. Titled Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze, January 7, 1894, or Fred Ott’s Sneeze, the film simply shows an employee hamming it up for the camera with a dramatized sneeze.

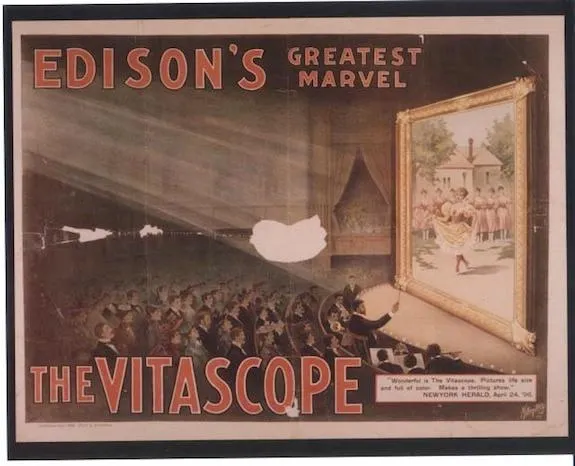

But if a man sneezes and no one hears it, is it really a sneeze? That was the dilemma Edison tried to solve as competitors began eating into his profits. In an attempt to synch sound and image, Edison added piped-in music via a phonograph to accompany the film. But the sound and image remained separate and often out of step, making it a less than enticing solution. Meanwhile, the allure of projected films that could finally entertain more than one person at a time called to businessmen in the industry. Another inventor, Thomas Armat, beat Edison to the punch. But Edison negotiated and bought the invention, changing its name from the Phantoscope to the Vitascope.

Filming news events, performances and tourism videos proved a profitable mix. But when audiences began to tire of the novelty, Edison turned to fiction-filmmaker Edwin S. Porter to create entertaining movies to be featured in the new storefront theaters known as nickelodeons.

As the popularity of these diverting films took off, Edison scrambled to own as much of the market as possible and protect his many related patents. After squaring off with a resistant competitor, Edison eventually negotiated a deal in 1908, according to the Library of Congress, that joined his company with Biograph and established a monopoly. His rise to the top, however, was short lived. Better technologies and more intriguing narratives were coming out of competing studios and though Edison continued to try to synch sound and image, his solutions were still imperfect. In 1918, Edison sold the studio and retired from his film career.

Though Hollywood is now synonymous with movie stars and big-name producers, it was actually Edison’s Black Maria in West Orange–the world’s first movie studio–that started the American film industry. Lintelman joked in his 2010 interview, “Most people can’t think of a place farther from Hollywood than New Jersey, right?” But Lintelman continued, “The American film industry was concentrated in that New Jersey, New York area from the 1890s until the 1920s. That’s when Hollywood became the movie capital of the world. Prior to that time, the most important factors were to be close to those manufacturing centers and investors in the markets. ”

Writing in an email, Lintelman, says, however, that he finds more similarities between online video culture than with Hollywood’s feature-length films. “It was a direct and democratic form of visual expression.” Viewers simply had to offer up their nickel to enjoy a brief diversion. Without audio or dialogue, the silent films could reach anyone, regardless of language. Though the subject matter could include spectacular news events or travel shots, most dealt with the daily experiences of man. “The filmmakers found humor in technological changes, transportation innovation, shifting demographics and social mores and the experience of city life,” writes Lintelman.

And viewers watched voraciously. After enjoying a kinetoscope film, people would mingle in the parlor space, discussing their favorites. With a variety of quick options in one place, viewers could create their own movie lineup and experience. “When you think about it,” Lintelman adds, “this is how we use the internet to view visual content today!”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)